Reports for the specific requirements of accounting firms to allow the particular firm to evaluate whether to accept or continue its client engagement, such as public and non-public company audits, tax, etc., with specific research strategies designed to assess the client’s financial and reputational risks, capitalize on opportunities and/or establish regulatory compliance.

The Scherzer Difference

Scherzer International (SI) has been providing specialized background screening reports since 1993. Our global clients include commercial and investment banks, private equity funds, and many of the largest law and public accounting firms in the world. With a distinct portfolio of scalable, purpose-specific reports for business transaction due diligence, client acceptance or continuation, employment and regulatory compliance, our services have proven essential for informed decisions and sustainable risk-management.

Scherzer International’s core philosophy is to deliver an outstanding report and client experience to every client we partner with. We distinguish ourselves as an industry leader through the following:

- Individualized progress updates and alerts of noteworthy information

- Easy to read reports with executive summaries

- Swift turnaround times

CLIENT ACCEPTANCE AND CONTINUATION

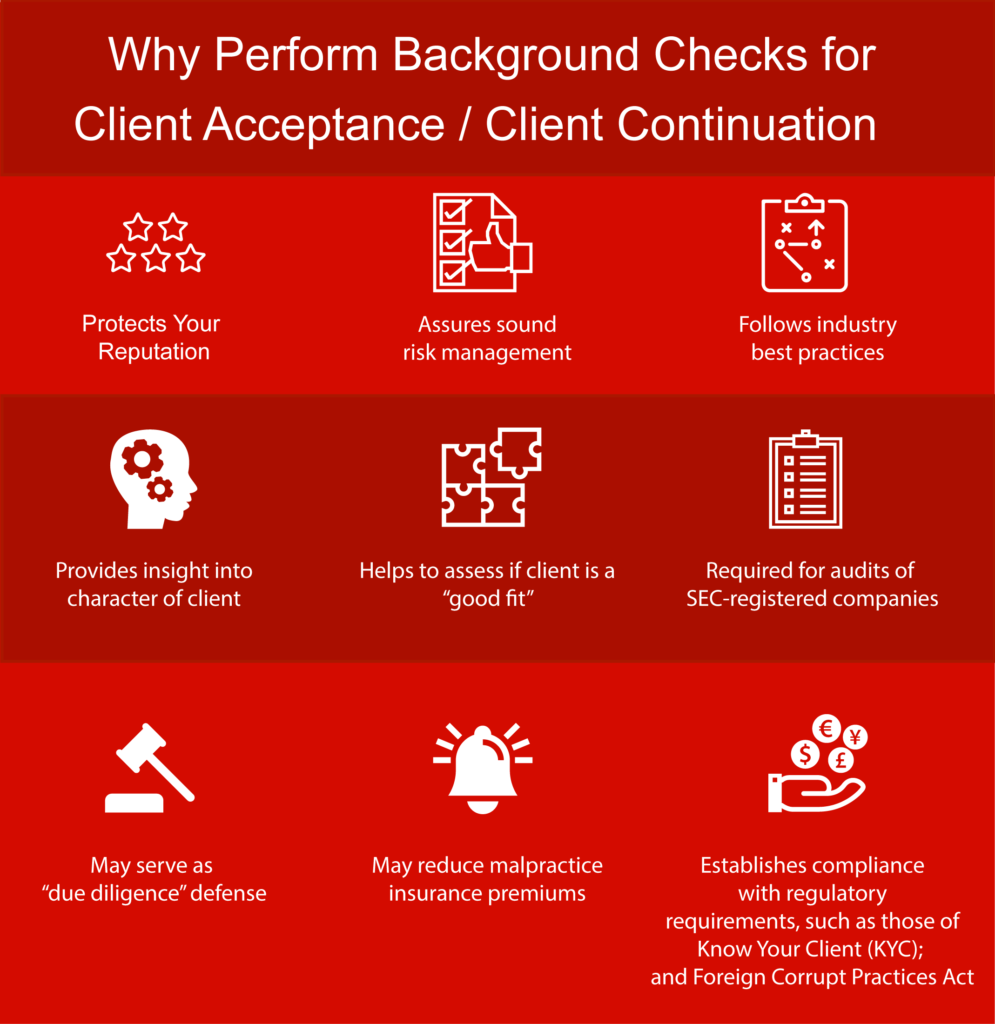

Background checks for evaluating risks associated with accepting a client or continuing an engagement have become a common practice of accounting firms. Driven by the requirements of U.S. accounting and auditing standards, pressure from professional liability insurers, federal and state statutes, case law that potentially expands liability to a broad user group of financial statements, and provisions of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, particularly as that act results in increased exposure under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (the “FCPA”), accounting firms, big and small, need to know their client.

Accounting firms conducting audits have long sought to narrow their liability to clients and to others relying on their statements, and to those who will be the direct third-party beneficiaries of their efforts. Gradually, legislatures and courts have expanded an auditor’s liability to allow those who are known or expected users of financial statements to recover losses resulting from an auditor’s negligence. Some cases and commentators suggest that auditing firms of public companies may occupy positions of public trust. As potential liability and risk have expanded, accountants have become more concerned about avoiding situations with unacceptable levels of risk.

In reviewing a broad range of cases that alleged negligence in an accountant’s work or where an accountant aided the client’s fraud or participated in the misconduct, the firm involved in the litigation could have avoided many of the problems if it had better information concerning the past history of its client, partner, supplier or employee. While not all litigation could be resolved or avoided, background checks are invaluable in revealing relationships that pose a high probability of future exposure.

AICPA Professional Standards

Since 2002, auditors of SEC-registered public companies have been required to conduct background screening before taking on engagements. Under auditing standards, mandating that firms adopt quality control standards, all accounting firms, whether involved in a SEC practice or not, are required to “establish policies and procedures for the acceptance and continuance of client relationships and specific engagements, designed to provide the firm with reasonable assurance that it will undertake or continue relationships and engagements only where the firm . . . has considered the integrity of the client, including the identity and business reputation of the client’s principal owners, key management, related parties, and those charged with its governance, and the risks associated with providing professional services in the particular circumstances. . . ”

The quality control standards refine this concept by adding that factors to consider regarding the integrity of a client include:

- the nature of the client’s operations, including its business practices; and

- information concerning the attitude of the client’s principal owners, key management, and those charged with its governance toward such matters as aggressive interpretation of accounting standards and internal control over financial reporting.

Management assertions are a critical factor in both attest and non-attest engagements and any blemish related to the integrity of key management may present risks, such as a key member of management having a criminal conviction, regulatory suspension or sanction. The philosophy that management exhibits in its conduct of the business also may reveal much about its integrity. While the quality control provisions do not specifically require background checks, in many cases compliance would be difficult to prove without them.

Moreover, under SAS 109 entitled Understanding the Entity and its Environment and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement, there is a requirement to consider whether information obtained from the auditor’s client acceptance or continuance process is relevant to identifying risks of material misstatement.

Insurance Industry Standards

Underwriters of the AICPA professional liability insurance program have stated that “careful client acceptance and engagement continuance practices can help firms manage the liability risks inherent in such audit relationships and control malpractice insurance costs.” Additional discussion of client acceptance and retention is included in the Statements on Quality Control Standards, which is applicable to both accounting and auditing practices. Insurers have an obvious interest in avoiding and reducing litigation. Like the AICPA and the SEC, insurers have focused particular attention on the client engagement process. While the underwriters do not go so far as to say that background checks would be a condition of coverage, there is a strong indication that at the very least, premiums will be affected and the absence of verification of the integrity of the firm’s client would be an adverse factor in making the coverage decision.

Legal Standards

Case law and accounting standards have defined an accountant’s duty of care to require that the accountant possesses the skills that an ordinarily prudent accountant would have and to exercise the degree of care that an ordinarily prudent accountant would exercise. These standards are reflected in the generally accepted accounting principles (“GAAP”) as promulgated by relevant authorities and generally accepted auditing standards (“GAAS”) as promulgated by the AICPA–an inadvertent breach of the duty of care will result in negligence. While not every minor deviation from the requirements of GAAS will have immediate liability, such deviations tend to be cumulative, and failure to conduct a background check when one is required may not result in a problem on its own, but when it is coupled with other failures, it can be a particularly damaging piece of evidence.

The standards that define an accountant’s liability to third-parties other than to its client depend on facts and circumstances and are not uniform among the states. For example, an accountant’s liability may vary in any of the following circumstances listed below in rough order from the greatest exposure to the least:

- where statements are included in an initial public offering;

- where statements are included in a secondary offering for a public company;

- where statements are included in a private offering, whether under Regulation D, Rule 144A or otherwise;

- where statements are issued with respect to a publicly traded company;

- where a company, public or private, has severe financial problems;

- where statements are issued for a significant privately held company;

- where statements are issued for other private companies; and

- where accounting work other than tax or an audit is performed.

In the first four circumstances, federal statutes are likely to apply. In many cases, these statutes characterize accountants as “experts” and specifically impose liability on buyers and sellers of the client’s securities. In these situations, accountants are liable for any material misstatement or omission in the financial statements that they audit, but they also have a “due diligence” defense that may protect them when they comply fully with the GAAP and all relevant statements of auditing standards.

When state law applies, the standards and liability to third-parties other than to the client can be different in a particular state, with at least three standards being commonly applied:

- the “functional equivalent of privity” standard;

- the “knowing user” standard as reflected in the Restatement of Torts §552 (a form of negligent misrepresentation); and

- the “reasonably foreseeable users” standard.

These theories are often in addition to assertions of fraud or violations of specific state or federal statutes. In almost all cases, plaintiffs are trying to establish that negligence alone is enough to hold an accountant responsible for all or a portion of the plaintiff’s loss. For the most part, courts have required something more than negligence. At a minimum, they have insisted on both a showing of negligence and a fairly clear use of the financial statements by the plaintiff that the auditor knew about at the time of the audit. In its most watered down form, this has been reduced to a “foreseeable” user that the auditor should have known about or anticipated.

Judge Cardozo’s opinion in Ultramares Corp. v. Touche, 255 N.Y. 170 (1931), established the basis of the functional equivalent of privity test. Under these standards, persons other than the client may not sue an accountant for professional negligence unless the accountant defrauded them, or actually knew that they would rely on the financial statement prepared by the accountant. In a much later case, the New York court further defined this standard and set forth the criteria needed to establish the liability of accountants on the basis of advice or services to clients when non-contracting third-parties claim injuries as a consequence of that advice:

- the accountants must have been aware that the financial reports they attested were to be used for a particular purpose or purposes upon which a known party or parties were intended to rely, and

- there must have been some conduct on the part of the accountants linking them to that party’s reliance.

The knowing user test is more expansive. While “Restatements of the Law” not adopted as formal statutes do not have the force of law, they can influence courts in interpreting the law and this appears to have been the case with §552 of the Restatement of Torts, which reads:

- “(1) One who, in the course of his business, profession or employment, or in any other transaction in which he has a pecuniary interest, supplies false information for the guidance of others in their business transactions, is subject to liability for pecuniary loss caused to them by their justifiable reliance upon the information, if he fails to exercise reasonable care or competence in obtaining or communicating the information.

- (2) Except as stated in subsection (3), the liability stated in subsection (1) is limited to loss suffered (a) by the person or one of a limited group of persons for whose benefit and guidance he intends to supply the information or knows that the recipient intends to supply it, and (b) through reliance upon it in a transaction that he intends the information to influence or knows that the recipient so intends or in a substantially similar transaction.

- (3) The liability of one who is under a public duty to give the information extends to loss suffered by any of the class of persons for whose benefit the duty is created, in any of the transactions in which it is intended to protect them.“

Under this standard, in addition to showing an accountant’s negligence, it is necessary to show that the accountant intended to supply the information to a particular third party and intended to influence that party or knew that the client had such intent. Commentators have indicated that this appears to be the standard in a majority of the states.

A small number of courts has held that accountants are liable for ordinary negligence to any user of the financial report whose reliance on the accountant’s certification was reasonably foreseeable at the time the accountant prepared the report. This standard is very broad and exposes auditors to potential claims from shareholders, market participants, creditors and others.

When an accounting firm conducts an audit, it does not necessarily know where a claim of negligence may arise or for that matter, where a plaintiff may reside or otherwise be able to bring a lawsuit. In effect, in many situations, auditors must assume the worst, even if that appears to be fairly remote. Under this approach, any form of negligence could result in liability to a very large class of potential plaintiffs who, with 20/20 hindsight, may be characterized as “foreseeable.” Accounting firms should take this into consideration when they assess risk and the cost-effectiveness of a background check. For firms involved with high-risk clients, transactions with public companies or involving public or private offerings and clients with multistate operations, this usually means that a thorough background screening at the outset is warranted and periodic updates are advisable, whether or not statements of auditing standards mandate the screening.

FCPA Standards

Under the FCPA, for the most part, the accounting firm’s client has the principal exposure, but a failure to note the exposure can compromise an audit and can also suggest a lack of adequate internal controls. The FCPA provides in part: “It shall be unlawful for any issuer . . . or for any officer, director, employee, or agent of such issuer or any stockholder acting on behalf of such issuer . . . corruptly in furtherance of an offer, payment, promise to pay, or authorization of payment of any money, or offer, gift, promise to give, or authorization of the giving of anything of value to any foreign official for the purpose of:

- (i) influencing any act or decision of such foreign official in his official capacity; (ii) inducing such foreign official to do or omit to do any act or violation of the lawful duty of such foreign official; or (iii) securing improper advantage;

- inducing such foreign official to use his/her influence with a foreign government or instrumentality thereof to affect or influence any act or decision of such government or instrumentality . . . in order to assist such issuer in obtaining or retaining business for or with, or directing business to, any person . . .”

Other provisions also make it unlawful to influence public officials or candidates for election. Defenses are limited, but they do include proof that the particular payment, gift or promise was lawful under the written laws of the foreign jurisdiction or was a reasonable and bona fide expenditure directly related to the promotion of a product or service or to the execution or performance of a contract with a foreign government or one of its agencies.

Adoption of comprehensive internal policies that are appropriately monitored and enforced coupled with risk-based due diligence will at least reduce the FCPA exposure. And under federal sentencing guidelines, it is clear that a risk-based due diligence effort, which focuses the greatest effort on the highest risk relationships will be considered a mitigating circumstance.

Conclusion

As discussed here, in many instances, auditing standards or laws require background checks. Accounting literature emphasizes that accountants must consider “audit risk” when performing audits for their clients, and in planning an audit, should focus on areas where the risk of misstatement is the highest. It is advisable that these principles be applied to the background check process. Even in situations not covered by an explicit requirement for background checks, the risk is often sufficient to dictate that a screening should be conducted.

Read more about: