Reports for general business-transaction due diligence—with specific research strategies and scope—are designed to allow the particular client to assess financial and reputational risks, capitalize on opportunities and/or establish regulatory compliance associated with investments, IPOs, partnerships, buyouts, joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, non-profit considerations, vendors and other third-party engagements.

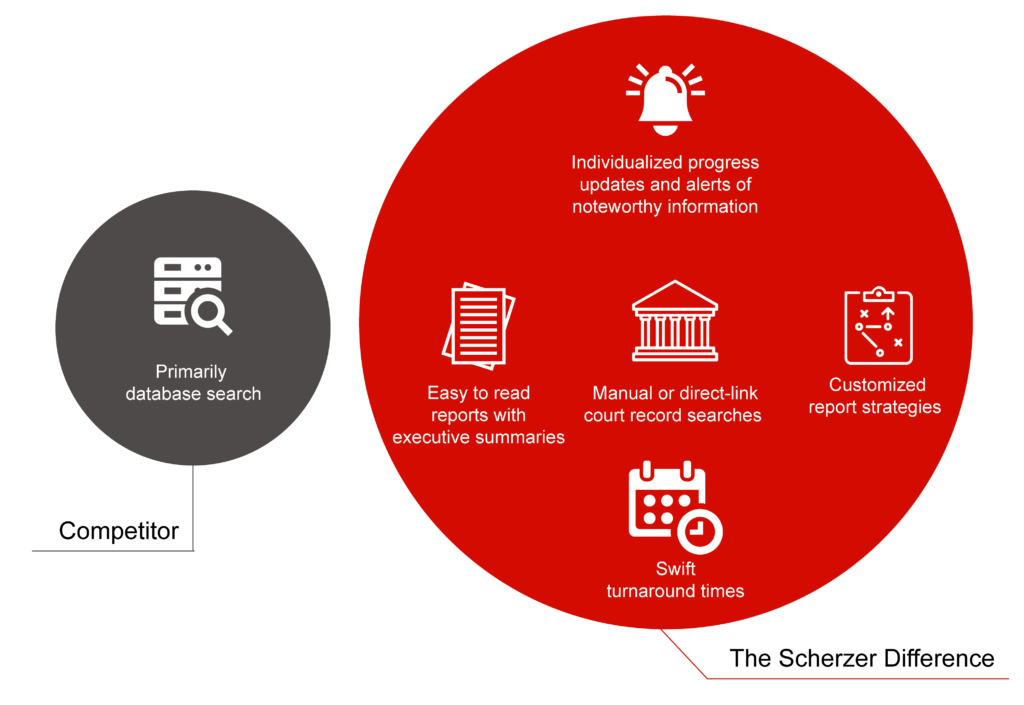

The Scherzer Difference

Scherzer International (SI) has been providing specialized background screening reports since 1993. Our global clients include commercial and investment banks, private equity funds, and many of the largest law and public accounting firms in the world. With a distinct portfolio of scalable, purpose-specific reports for business transaction due diligence, client acceptance or continuation, employment and regulatory compliance, our services have proven essential for informed decisions and sustainable risk-management.

Scherzer International’s core philosophy is to deliver an outstanding report and client experience to every client we partner with. We distinguish ourselves as an industry leader through the following:

- Individualized progress updates and alerts of noteworthy information

- Customized report strategies

- Swift turnaround times

- Easy to read reports with executive summaries

A handshake is never enough

Performing due diligence in connection with a business transaction is now routine, whether the transaction involves commercial lending, private equity or venture capital funding, merger or acquisition, setting up a partnership, or evaluating a non-profit.

“Due diligence,” in a broad sense, refers to the level of judgement, care, prudence, determination, and activity that a person would reasonably be expected to do under particular circumstances. Depending on the risk involved, the process will often include some level of background screening on the company and/or its principals to obtain the intelligence necessary for an informed business decision.

Looking at the people involved

Whether a background check is performed internally or outsourced to a third-party, its elements and focus will depend on the risk involved to determine the potential borrower’s credit worthiness. Background checks are rarely performed on large publicly-traded companies, but Scherzer’s experience shows that most specialty lenders and investors dealing with privately held companies conduct searches on the key members of management and often the entity itself. Most financial services companies outsource the process, and some pass the cost of the background report to the borrower. Commercial banks also perform background checks as part of the underwriting process, but limit the screening to the borrower and guarantor, and the bank absorbs the cost of the diligence. While the cost of the background report is always a factor, it is less so when the risk of default is perceived to be greater than the norm.

International background screening

Expanding the due diligence process to include international background checks when the principal has a significant foreign history or the company is a non-U.S. entity is essential to sound risk management.

Availability of Information

The scope of the background check, while taking into consideration the risk level of the transaction, will depend on the information that is available in the public domain, and the customs, culture, and laws of each country. What may seem perfectly routine and acceptable in the United States may confuse or offend those in other countries. For example, credit checks are virtually unheard of abroad.

The collection of criminal information can also present logistical challenges. Many countries do not have an organized court system, and, records, if available, must be searched on a regional or town-by-town basis, or at multiple agencies (such as the police station, the court venue or a government agency, for example). Certain countries offer what is known as a “police certificate” which provides confirmation of the information about a subject found in police records.

Taking a “reasonable” approach to international background checks is particularly important in emerging markets, where many public records are unavailable or unreliable. The situation is improving, however, as it is now possible to obtain from almost any country business registration information regarding the owners and directors of a corporate entity, with the exception of the secrecy jurisdictions, such as the British Virgin Islands where ownership information remains inaccessible to the public. Most jurisdictions also maintain lists of debarred persons and companies. This is especially common in countries with well-regulated stock markets, such as Hong Kong and Singapore. Singapore also allows access to criminal records, while many emerging market jurisdictions consider an individual’s criminal record to be private.

Civil litigation records too are becoming more available; however, local knowledge and an understanding of the judicial system are critical to obtaining information legally. Searches in China, for example, are especially complex, as the filings can be held at either county, municipal, provincial or state level.

Media searches are possibly the most significant element of any international background check. If these checks are not performed locally, they at least should be conducted in the native language in the international databases available in the United States and the Internet.

Legal Compliance – Privacy Laws

Information privacy or data protection laws prohibit the disclosure or misuse of information maintained about private individuals. According to a report published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 66% of countries have enacted data privacy protection laws; 10% have legislation in draft form; 19% have no such laws, and 5% have no data available.

Arguably, the European Union (EU) has set the bar for privacy protection of personal data with its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that went into effect in May 2018. The GDPR’s holistic view of personal data, defined as anything that can identify an individual — including a person’s address and image — is seen as the gold standard, differing from the patchwork of laws in the United States and some other countries.

Under the GDPR, global companies that transfer personal information of individuals located in the European Economic Area (EEA) to the U.S. must have a legal mechanism for these transfers. Until recently, hundreds of U.S. multinationals relied on the EU-US Privacy Shield (the “Privacy Shield”) framework to meet the GDPR requirements. Then, in July 2020, an unexpected ruling was handed down by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Ltd and Maximillian Schrems (“Schrems II”) that invalidated the Privacy Shield which had been in place since 2016.

Now companies that subscribed to the Privacy Shield must find another GDPR-compliant solution for the transfer of data. The European Data Protection Board indicated in its July 23, 2020 FAQs that it will not be providing a grace period as the authorities had done for the EU-U.S. Safe Harbor framework following the “Schrems I” decision. Notably, the CJEU’s decision expressly stated that the standard contractual clauses (“SCCs”) previously promulgated by the European Commission are still a valid tool for data transfers from the EU to the United States. The SCCs are sets of contractual terms and conditions that the controller and the processor of personal data both execute to comply with GDPR’s requirements. The CJEU did not directly reference binding corporate rules (“BCRs”) which are used for intragroup data transfers and require prior approval of the competent data protection authority. For now, this means that BCRs remain a valid transfer mechanism under the GDPR as BCRs are of a similar nature to SCCs (they are both considered an “appropriate safeguard” pursuant to Article 46 GDPR). For some situations, an alternative is to look to the narrow derogations under Article 49 of the GDPR, such as to perform a contract, for “legitimate interest” purposes or base the transfer on the subject’s explicit consent.

Asset searches

Getting bank and investment account records of defaulted commercial borrowers

Asset searches, which may include bank and investment accounts, are not illegal; however, certain actions to obtain this information, such as pre-text calling are illegal. Although there are methods that can be used to obtain financial information covertly, most, if not all, are questionable and often futile. There is no clear way for anyone other than the account holder, a designated representative or a party with a valid court order to obtain account information without violating the law. And getting an account balance may be of limited value since it is transitory, depending on the transactions related to the account which are being processed at any given time.

A long list of potentially applicable federal laws and an even longer list of state laws are directed at protecting the privacy of consumers. For the most part, consumers are defined in the laws and in interpretative decisions as individuals consuming goods or services for personal or household use. For example, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) prohibits obtaining customer information from a financial institution under false pretenses and imposes on the institution the obligation to protect customer information. Under the GLBA, a customer is defined as an “individual.” This is essentially the same as the definition of a consumer under the Fair Credit Reporting Act. However, in making the distinction between an individual and a business, there is authority that finds sole proprietors, partnerships of five or fewer persons and other small business owners to be consumers.

As a general matter, information concerning a business is governed by the contract between the financial institution and the business customer. This does not mean that the bank or other financial institution can give access to anyone about an account or that pre-text calling to obtain information about a business account would be lawful–it just means that the specific consumer protection regarding these matters would not apply.

Searching for assets in foreign countries brings its own problems, as many countries’ privacy laws are more restrictive than those in the United States. Potential liability under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) also exists if, for example, a financial institution used a third-party that obtained information about a defaulted borrower’s assets by illegal means, such as bribing a banking or government official. The FCPA holds that “any bribery of a foreign official by an agent of the principal to benefit the principal can be attributed to the principal if the principal knew or should have known that the bribery was going to occur.”